A theatrical work can often tell us more about the time it was written in than the theme its author intended. Take the case of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. The story revolves around a barber, Sweeney Todd, who selectively killed his clients, sending their bodies down through a trap door to his accomplice, Mrs. Lovett, who used the bodies for making meat pies. The fates of two innocents, a sailor (Mark originally, then Anthony later) and the inaccessible girl with whom he falls in love, Johanna, become entwined with the skulduggery of Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett.

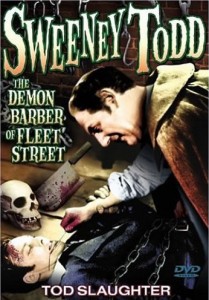

In 1936, director George King brought Sweeney to life with Tod Slaughter as the barber who cut a little too close, and Stella Rho as a totally unlovable Mrs. Lovett. (Available from Alpha Video, or Netflix.)

In 1936, director George King brought Sweeney to life with Tod Slaughter as the barber who cut a little too close, and Stella Rho as a totally unlovable Mrs. Lovett. (Available from Alpha Video, or Netflix.)

This rendering of the story is a bloody, yet funny, macabre tale that doesn’t take itself too seriously. The presentation of the story also takes some of the nastier edges off. Even though about “murder most vile,” the story is bookended by a tale of a modern-day (1936) barber and his customer.

The modern-day barber relates the tale of Sweeney to his customer with around-the-campfire ghost-story enthusiasm. In the closing segment, the customer watches the barber sharpen his blade, gets spooked, and goes running down Fleet Street in fine Laurel and Hardy/Keystone Cops fashion.

Further, the content of Mrs. Lovett’s meat pies is only implied. Cannibalism wasn’t cool and, as I recall, when I saw this film on my parents’ black-and-white TV somewhere back in my pre-teen days, I believe I totally missed the whole people-pie concept.

In this version of the story, the sailor is the hero, ultimately rescuing the fair Johanna from Sweeney’s clutches, and bringing an end to his evil. The theme is quite clear: young love and purity can overcome evil. From his evil laugh to his nasty demeanor, Sweeney is totally, unforgivably evil.

Skip forward 40 years to the 1970’s. (You may want to close your eyes now and imagine Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire” video.) No longer is cannibalism so heinous we can only imply it; now, we can sing about it. But out-of-the-closet cannibalism is perhaps the least significant of the zeitgeist-inspired changes to the story.

The musical Sweeney Todd opened on Broadway in 1979, based on the legend and on the 1973 play, The String of Pearls, by British playwright Christopher Bond. My observations are based on the 1982 motion-picture-of-a-play, available on DVD from MGM and RKO/Nederlander Productions. It stars George Hearn as Sweeney and Angela Lansbury, who debuted the role on Broadway, as Mrs. Lovett. (Lansbury comes across as a British-psycho Lucile Ball and is quite charming.) The 1936 version ran one hour and seven minutes, but the musical lasts for two hours and 20. Is the difference just singing? No, the plot has turned inside out and around itself in most revealing ways.

The bookends are gone, and now we meet Sweeney not lurking in the shadows waiting for the fleet to come in, but himself disembarking from one of the ships. “Sweeney Todd” is just a pseudonym for a Mister Benjamin Barker, returning from a fifteen-year stay in an Australian penal colony.

Sweeney-Benjamin returns to his old barber shop and connects with Mrs. Lovett, and we find that far from being a creature of unrepentant evil, Sweeney is (here it comes, zeitgeist fans) a victim! Further, he is not just a victim of fate; he is a victim of a corrupt judge and his henchman policeman. It is his desire for revenge against a self-serving, elitist power structure that drives Sweeney to his crimes and Mrs. Lovett to a healthy bottom line.

Sweeney-Benjamin returns to his old barber shop and connects with Mrs. Lovett, and we find that far from being a creature of unrepentant evil, Sweeney is (here it comes, zeitgeist fans) a victim! Further, he is not just a victim of fate; he is a victim of a corrupt judge and his henchman policeman. It is his desire for revenge against a self-serving, elitist power structure that drives Sweeney to his crimes and Mrs. Lovett to a healthy bottom line.

Oh, my. The class-warfare hairs on the back of my neck stand up and get all tingly.

To be fair, in this version, too, Sweeney Todd gets what’s coming to him in a Shakespearian death-fest, but not until he and Mrs. Lovett have served up plenty of justice pie. And, oh yes, young love does triumph, but it’s kind of an afterthought. The theme: life is tragic and evil is a social phenomenon. Poor Sweeney.

Fast-forward another 30 years and we have Johnny Depp, the generation-X version of Errol Flynn, sharpening his blade. Any negativity in the following paragraphs is purely directed towards the zeitgeist, not the film. Since Planet of the Apes I’ve been apprehensive about what Tim Burton could do to someone else’s story. Sweeney, however, is right up Tim Burton’s dark alley, and it is a textbook rendering of the stage play on the screen. Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter more than do justice (cinematically speaking) to Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett.

But what has the zeitgeist done to the story this time? It is the Ever-Diminishing-Hero syndrome. In the 1936 version, the hero-sailor is really a hero, vanquishing African natives and later defeating Sweeney. In the stage-play, he has less of a role, but is still worthy of being called a hero. In the 2007 film, he is reduced to a somewhat ineffectual dreamer with only boy-band masculinity. Also (relying on my memory), I believe one song/sequence was also dropped from the 2007 version, one in which the sailor and Johanna bond and plan their escape.

The zeitgeist of 2007 has turned the straightforward morality play of 1936 on its head. It leaves love diminished, with Johanna so badly damaged it is unlikely that love will triumph. We are left with tragic, sympathetic Sweeney in a pool of his own blood. And the sailor – his last name was Hope — is all but gone.