(Originally published on blogcritics.org)

At this month’s Producers Guild of America “Produced By Conference”, a distinguished group of filmmakers tackled the question “Do producers bring anything to the creative process?”

Maybe it doesn’t apply to every producer, but these gentlemen bring a lot. David Pickler, former CEO or United Artists and producer of Lenny, The Man with Two Brains, and The Crucible, led the “Creative Alchemy” discussion. The panel members who shared their move-land “war stories” included Lawrence Gordon (Die Hard, Field of Dreams, The Rocketeer), Douglas Wick (Wolf, Stuart Little, Memoirs of a Geisha) and Bruce Cohen (American Beauty, Big Fish, Pushing Daisies).

Maybe it doesn’t apply to every producer, but these gentlemen bring a lot. David Pickler, former CEO or United Artists and producer of Lenny, The Man with Two Brains, and The Crucible, led the “Creative Alchemy” discussion. The panel members who shared their move-land “war stories” included Lawrence Gordon (Die Hard, Field of Dreams, The Rocketeer), Douglas Wick (Wolf, Stuart Little, Memoirs of a Geisha) and Bruce Cohen (American Beauty, Big Fish, Pushing Daisies).

Participants agreed that there are two major areas, beyond the day-to-day business aspects of movie making, where producers contribute. The first is handling the unexpected – sometimes to the extent of saving the project from destruction.

Douglas Wick said that he saw the producer’s main job as holding it all together and solving every conceivable problem. “One day I  got a call that only one of the two animal actors, cats, could come in for the shooting.” he recalled. “It seems the cat’s ass was about to fall off. No, really, there is a condition resulting from stress which causes cats anuses to swell up. So there I was on the phone with a veterinarian figuring out what to do about a cat’s ass”.

got a call that only one of the two animal actors, cats, could come in for the shooting.” he recalled. “It seems the cat’s ass was about to fall off. No, really, there is a condition resulting from stress which causes cats anuses to swell up. So there I was on the phone with a veterinarian figuring out what to do about a cat’s ass”.

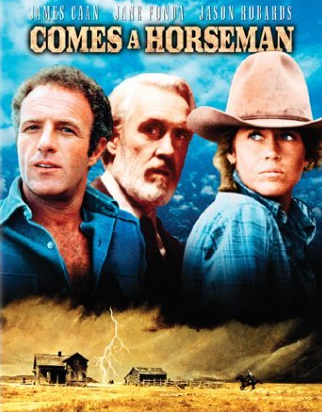

That wasn’t the only animal challenge Wick had to deal with. The very first movie he worked on was Alan J. Pakula’s award winning Comes a Horseman (1978) with James Caan and Jane Fonda.

Wick explained that they had a scene where they needed a cattle stampede. “We were shooting day-for-night so we needed a clear sky”, he said. “We had the cattle on the hill with the wranglers behind them. We sat there all day waiting for the clouds to go away so we could shoot.

“Finally, in the late afternoon, the skies cleared. The director yelled ‘Action’. The wranglers set off all kinds of loud noises and explosions. The cattle started down hill, and then two of them dropped dead from heart attacks. We had gotten the wrong kind of cattle. They were very sedentary and couldn’t take the excitement. I had to get tougher cows.”

Not all producer problems are the four footed variety. Most efforts producers make to save a project involve people and money.

Lawrence Gordon produced 48 Hours with Nick Nolte and Eddie Murphy. Gordon recalled that he had to intervene with the studio. “I got a call from execs at Paramount one day when we were several weeks into the project”, he said. “They wanted to fire Eddie Murphy. They thought he wasn’t funny. Keeping things like this from happening is how we protect the project.”

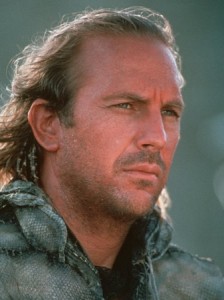

Then there are money problems, for which Gordon has one word: “Waterworld”. The 1995 sci-fi epic with Kevin Costner used up money like it was water.

Gordon remembered, “Our first day of shooting; we have this huge set covered with hundreds of extras. It took us all day to set up. I’m on a filming boat behind Kevin Costner’s boat: ‘Action!’ Then somebody starts yelling ‘Cut, cut. We need the divers and the zodiacs.’ In all my years in film, I had never heard the words ‘divers and zodiacs’ on a set. Someone had cut an underwater cable. You can’t budget for that but you have to pay for it.”

And people who aren’t even in the film can cost you money, too. “Later in the filming we were doing a shot where we were waiting for the sunset,” Gordon said. “’Action!’, then ‘Cut, cut, There’s some boat floating into our scene.’ We sent someone to talk to them and it turned out there were three people on the boat, totally stoned, who wanted to see the sunset. They wouldn’t move. I even sent a 500 pound Samoan over to talk with them and they still wouldn’t move. We lost that day, too.”

The second area producers contribute to, besides saving a project, is to make sure the project is worth saving. Bruce Cohen described it as getting “the director’s vision on the screen”.

He pointed out, “If you’re working with Stephen Spielberg you just have to keep things out of his way. But sometimes other directors may not have a clear vision. You’ve got to get inside of their heads — figure out what they do well and where they need help and focus on that.”

Doug Wick agreed but said that sometimes you have to begin the creative process without a director as he did with the 1988 rom-com “Working Girl”, starring Harrison Ford and Sigourney Weaver.

Wick said, “When I was producing Working Girl, we went through writers and a series directors but no one was generating the excitement I felt about the project. We sent the script to Mike Nichols and then I went to see him. As soon as he started to talk about the story, I knew he had the vision. After that my job was easy.”

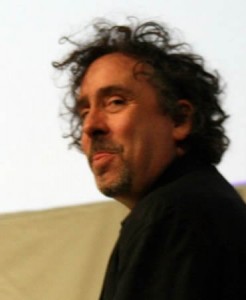

Bruce Cohen agreed, but went a little farther in his assessment of the creative alchemy the producer could cook up. To illustrate, he shared a story about working with Tim Burton on Big Fish, the 2003 fantasy which starred Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney and introduced the film world to Miley Cyrus.

“Burton is probably the most complete auteur working now. His vision is in every frame of every scene — it’s absolutely him,” he said. “He loves to play the role of the mad genius. He is always pacing — in preproduction and in production, which makes it hard to have a conversation with him — which I eventually realized was the point. So when I had an idea, and this was always true, I didn’t know if it was better, or just different.”

Cohen was reluctant to “give Burton notes”, but about a week into the filming he gave it a try. “I did have an idea that I thought was very ‘Tim Burton’,” he said. “I came out onto the set and at first he looked at me like ‘What are you doing standing out here on the set next to me?’ I whispered my idea in his ear and then he smiled and used the idea. That happened twice more during this film. That’s all the help I gave him.”

David Pickler summed up the session and offered advice to producers, writers and anyone else “who wants to make things happen in Hollywood.”

“One of the things you have to realize is that in this business” he said, “people will say ‘no’, and not know why. Saying “no” is safe. At United Artists we never said ‘no’ without knowing why. There are reasons to say ‘no’. But don’t take ‘no’ unless you can get a reasonable answer as to ‘Why?’”

Check back for more coverage of the “Produced By Conference”, including an interview with Seattle filmmaker, Peter Ong Lin.